July 2001 (Part 2)

SELECTION OF QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS

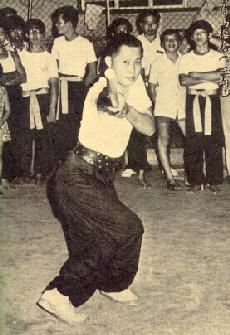

Sifu Cheong Wing Kwang demonstrating the Shaolin Staff

Question 1

I don't feel as though my training is going as well as it should. I feel as though slowly with time, your teachings have become more and more distant, my training results less and less satisfactory and my self doubts keep growing. Things that seemed so easy in your presence and in the weeks after being with you have become difficult to imagine.

— Jeffrey, Switzerland

Answer

For me, your present “lack” of progress is expected. In fact I hinted to you a few times, though you probably might not be aware of the hints then. You may recall my remarks like “spread out your practice”, “don't let initial enthusiasm boils over too soon”, and “don't be discouraged if suddenly you find yourself not progressing”.

Yours is what I would call “the fast learner's syndrome”. It is similar to the “plateau” in the learning process of ordinary students, except that the “fast learner's syndrome” comes much faster, is more dramatic, and is more frustrating.

The reasons for this syndrome are as follows. Skills and force need time to be developed — otherwise your body systems would not cope with the new and greater levels of skills and force. But being a fast learner, you acquired in a few weeks what it would normally take a few months to acquire. Hence, Nature intervenes for safety reasons.

Moreover, fast learners have very high expectations. Even when there is progress but if the momentum slows down, they feel relatively that progress has stopped. Also, fast learners are impatient. This is logical as they can learn in a few minutes what ordinary people might take a few hours to learn. Hence, when progress has slowed down or has come to a “plateau”, they become frustrated.

I was a fast learner too. But my training was different. I was trained in a traditional way, where I was used to practise — as oppose to learn — under the master's supervision, and often on my own without his supervision. I did not know what or when my master would next teach me; I only knew I had to practise and practise.

And I was used to the traditional advice given by past masters: “don't worry about benefits, just practise and the benefits will come when the time is ripe.” This advice was meaningful when it came from real masters, who clearly exhibited the qualities I wished to emulate.

Such a tradition somehow softened the “fast learner's syndrome”. Your training was different. You learned in three days material sufficient for a year's training, and you attained the targeted level not in a year but in three months.

But I too had “fast learner's syndrome”, though it was not as intense as yours. I remember, for example, that when my master, Uncle Righteousness, first taught me techniques of using double daggers, he remarked to other students and friends, “He learns so fast. He will have learnt the whole set in a week when others would need many months.” But I didn't learn that double dagger set in a week. “Fast learner's syndrome” set in and my progress rate dropped; Uncle Righteousness also commented on the drop of progress. I learned that set in a few weeks — slower than expected but still faster than most students.

Question 2

Somehow I think that my early results were “too good” and I expected or at least hoped that my progress would continue as it went along for the second half of last year. If I didn't have anything to compare it to I'd probably be happy to be able to perceive and increase my chi flow so easily but it's frustrating to have to admit that my training now is much less than half as good as it was in December.

Answer

You were right in your observations.

Do you remember I said that even if your effects practising on your own were one-eighth of what you experienced at the December intensive courses, your results would still be better than the great majority of practitioners in the world?

To outsiders, this statement is presumptuous and disparaging, but I believe it is valid. The great majority of chi kung practitioners, for example, have not experienced chi flow; the great majority of Tai Chi Chuan practitioners do not know how to defend themselves; and the great majority of kungfu practitioners do not know internal force. Yet you know and have experienced all these. Each time you practise, you are enhancing these fundamental skills — even if at times the progress could be painstakingly slow.

On the other hand, the “plateau” in your training can be a preparation for a sudden break-through.

An example can be seen in my learning from my other beloved master, Sifu Ho Fatt Nam, the kungfu set called “Four Gates”, which was reputed to be the fundamental kungfu set taught in the past at the Fujian Shaolin Temple. My learning and progress was fast, then suddenly “fast learner's syndrome” set in. I practised daily the same set for many months, and was frustrated at my lack of progress. Not only my master did not teach me anything new, he did not even look at my training. Then, one day he told me, “Now link the patterns smoothly, fast, in one breath.”

It was not even necessary for my master to demonstrate to me! When the time was ripe, just a statement was sufficient. I acted on his advice and progressed beyond recognition. Many doubts just melted away with that awakening. I suddenly realized, and was even able to accomplish the feat myself, why kungfu masters could fight in such speed and precision and yet not short of breaths. More significantly, that advice enabled me in later years to defeat my opponents in sparring and in real fights in such speed that they did not know where my movements came from.

As a great teacher he was, my master was actually monitoring my progress all along; he waited for the right moment to give just the right instruction. Had he explained or demonstrated to me earlier, his words and his demonstration would be beyond my understanding and performance.

Question 3

Throughout the last months I've been sick a few times and that great feeling of chi flowing through my body has become less and less evident.

Answer

I am surprised that you were sick not just once but a few times. You shouldn't (but you were). I do not know why, but I can offer a few possible reasons, as follows.

- You have practised wrongly — this is most unlikely.

- A change of life-style, environment, etc created disease-causing factors which even your chi kung practice could not overcome — this is unlikely.

- Your sickness is part of your cleansing, or developmental task. Some literature describes this phenomenon figuratively: in the process of becoming a master, the student dies, parts by parts, then is born again. Remember, what you are practising is not just some exercise to maintain health and to defend yourself, but a complete programme for the highest physical, emotional, mental and spiritual fulfilment. This could be a likely reason.

- Your sickness is Nature's ways to prevent your too-quick progress from harming you — this is the most likely reason.

Your chi flow has become less evident because you have become familiar with it. It has become second nature to you.

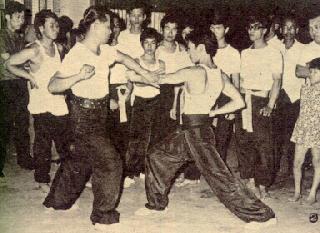

Application of Shaolin Kungfu. As the attacker executes a left thrust punch to Sifu Cheong (left), Sifu Cheong moves slightly to his right side and sweeps away the attack with his left hand.

Question 4

Also, could you please tell me which courses you'd recommend me attending. As far as my summer vacation goes I could come for the Chi Kung in Ireland, the intensive Chi Kung in Sungai Petani, the Chi Kung and Tai Chi Chuan in Malaga or any combination of the three.

Answer

Although it is beneficial, considering the time and money involved it is not necessary for you to come for my chi kung courses and Tai Chi Chuan courses. But it is very beneficial for you to attend my Intensive Shaolin Kungfu Course, especially in Malaysia, if you follow my advice to focus on Shaolin Kungfu amongst the three arts.

Remember what I have said? Speaking relatively and in jest, chi kung is for lazy people, Tai Chi Chuan is child-play, Shaolin Kungfu is for those what want the best and are willing to work very hard for it.

For dedicated fast learners like you, Shaolin Kungfu is the best choice. While the skills (including force) in Shaolin Kungfu need time to develop and may cause you “fast learner's syndrome”, the vast range of techniques will keep you busy even when you learn fast.

And the great demand needed in the development of Shaolin skills will be challenging even to fast learners. You may be frustrated, but for a reversed reason. In chi kung you become frustrated because you remain at a plateau for a long time after achieving a specific objective, such as massaging your various internal organs. In Shaolin Kungfu you become frustrated because you remain at a plateau not after but before achieving a specific objective, such as breaking a bottom brick with a palm strike without breaking the brick on top.

A good way to overcome the “fast learner's syndrome” is to become a Shaolin Kungfu instructor. It is not for no good reasons that I suggested to you to take up Shaolin Kungfu and become an instructor. But as a good student you said you preferred to spend more time practising to be more proficient first.

Becoming an instructor in the Shaolin Wahnam network is both a privilege as well as part of the training programme for a promising student. Given present conditions, it is an excellent way for him to have sufficient methodical sparring practice, an essential part of the training programme.

As an ordinary student he may have difficulty finding suitable sparring partners, but as an instructor he has to spar with his students and assistant instructors. Kungfu comes to life in sparring, and as training objectives in kungfu are many and varied as well as demanding, “fast learner's syndrome” usually disappears. Of course, becoming an instructor calls for more dedication and responsibility than that required from an ordinary student.

In chi kung, for example, having achieved an objective such as being able to direct chi to a particular part of your body, further training results in greater skill in this ability but its effect is not so easily perceived. “Fast learner's syndrome” therefore sets in. But in kungfu when you are an instructor controlling training conditions, you can have variety in your objectives for your own development while contributing to your students' progress.

Let us say you are teaching your students a specific technique to counter a particular kick. You apply the kick to a student and he counters with the technique. Because your skills are higher you can see quite clearly how he counters. Gradually you do not merely observe his counter but also certain weaknesses in his movements. Each time he counters, although he makes similar movements, he may exhibit different weaknesses. For example, on one occasion his balance may be poor, on another occasion his form may be awkward, and on a third occasion his movements may be staccato.

Next you exploit his weaknesses. Hence, although he knows the right technique to counter your attack, you still defeat him — with the first attack or with a follow-up attack issuing from his particular weakness. And you regulate your speed in such a way that you overcome him just at a right time.

You explain to him that he is defeated not because he does not know the right technique to counter, but despite his knowing he cannot counter effectively because you are more skilful, and in this case you are able to exploit the weakness he makes in his counter. So you teach him to overcome his weakness, thus improving his skill.

When your student has corrected his weakness he will be able to counter your attack effectively. Then you increase your speed. Now, even he has no technical weakness in his counter, he is still defeated by you. You explain to him that in this case you defeat him in speed. So you help him to increase his speed.

Hence, teaching kungfu is very interesting. Both you and your students benefit. There are more opportunities for you as an instructor to vary your goals that the “fast learner's syndrome” can be minimized.

Question 5

In regards to your statement that true masters are hard to find nowadays, could you tell me if you know of Grandmaster Cheong Wing Kwang of the Hung Gar style who is in Malaysia. Apparently he is a 4th generation student of Wong Fei Hung, the founder of the Cheong Wing Kwang Institute and the Gao Pei Physical Culture Association in Malaysia. Your opinion is much appreciated,

— Jason, UK

Answer

Yes, Sifu Cheong Wing Kwang is the 4th generation successor of the famous Southern Shaolin patriarch, Wong Fei Hoong. Sifu Cheong's teacher, if I am not mistaken, is Sifu Song Siew Po, who in turn learned from the famous master Lam Sai Weng, an outstanding disciple of Wong Fei Hoong.

Despite, or more correctly because of his kungfu mastery, Sifu Cheong whom I am personally acquainted with, is a gentle, soft-spoken man. He is well known for the famous Shaolin kungfu staff, known in Cantonese as Ng Long Pat Kua Kuan, and the advanced Shaolin chi kung known as Golden Bell.

Sifu Cheong lives in Kuala Lumpur, the capital of Malaysia. Due to historical, geographical and cultural factors, Malaysia happens to house some very good kungfu masters who, being direct successors of the last real kungfu warriors of China who escaped overseas during the Qing Dynasty, still preserve traditional kungfu forms. Elsewhere, including in China today, these traditional kungfu forms are in danger of being replaced by modernized wushu.

Question 6

Have you heard of the martial art known as Sho'u Sh'u? It is said to be 4200 years old and consists of a seven animal systems — Bear, Tiger, Mongoose, Crane, Mantis, Cobra, and Dragon.

— Krahe, USA

Answer

I am sorry I have not heard of a martial art called “Shou Shu”.

In Chinese, “shou shu” means techniques of the hands. This is probably the meaning of the martial art you referred to.

As far as I know, the oldest form of martial art, one with a proper name referring to a coherent system of philosophy and practice for combat, is Shaolin Kungfu. Shaolin Kungfu was initiated by the great Bodhidharma at the Shaolin Monastery in China in the year 527, which is about 1500 years ago.

This does not mean that before 527 there was no martial art. Martial art was older than civilization and history. In other words, before men practised agriculture and lived in settlements, and before they knew writing, they already had devised ways to fight better, alone or in group warfare.

But martial art at that time was personal and individual, not institutionalized. Martial art was then a common noun or a collective noun; there were no proper nouns like Shaolin Kungfu, Chen Style Taijiquan or Shotokan Karate to denote specific schools or institutions of martial art with their respective characteristic philosophy and practice.

It was at the Shaolin Monastery that martial art was institutionalized for the first time in its long history. This means a particular philosophy and practice of martial art was designated and subsequently developed as Shaolin martial art (or Shaolin Kungfu), whereas all other martial art was just called martial art or by any common names the respective people generally referred to ways of fighting.

Considering that many systems of martial art today have a history of less than a hundred years, and many ways of fighting in many parts of the world, such as boxing and wrestling in the West, are still not institutionalized, Shaolin Kungfu as a coherent system of martial art has a very long, and the oldest, history — about 1500 years. Hence, it is a mistake to say that Shou Shu, as a coherent system of martial art, has a history of 4200 years.

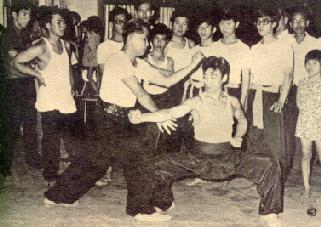

The attacker changes from his Bow-Arrow Stance into a Sideway Horse-Riding Stance and sinultaneously executes a right punch at Sifu Cheong's dan tian (abdominal energy field). Sifu Cheong shifts his body slightly backward to avoid the punch, sweeps away the attack with his right tiger-claw, moves his right leg slightly forward, and swings a reverse-fist at the attacker's head.

Question 7

I have several health problems. There is always a discomfort in most parts of my body such as tightness and rigidness. I try to do meditation, but I can't because I cannot concentrate. Instead, the discomfort will distract me.

Moreover, there is also some sort of itchiness from inside the body. Not on the skin, but from somewhere inside the body that can be unbearable. Apart from that, my thoughts are often fuzzy and unclear. Do you think you can help and that there is some qigong that can cure me? How much does it cost?

— Tan, Malaysia

Answer

Yes, I can help you to overcome your problems. Although conventional Western medicine may not offer any solutions to your problems, from the chi kung perspective, they are inter-related and can be overcome comparatively easily.

You should attend my Intensive Chi Kung Course to be held in Sungai Petani. In the course you will acquire fundamental chi kung skills and techniques which you can competently practise on your own. If you practise for about 15 minutes a session, two sessions a day, you should be able to overcome your problems in a few months. Overcoming your problems is only a stepping stone; you would gain other wonderful benefits.

Please refer to Intensive Chi Kung Course. The fee for the Intensive Chi Kung Course is US$1000. Depending on your perspective, it is very cheap or very expensive. If you compare my fee with what most teachers charge, it is exorbitant; if you compare it with the benefits you get, it is very cheap. The course is satisfaction guarantee; if you are not satisfied with the course, you need not pay any fee. Please apply to my secretary if you wish to attend the intensive course.The tightness and rigidness in your body is due to muscular tension. Some energy is locked up in your muscles, and it has become “stale”. “Fresh” chi finds it hard to flow smoothly through the tissues of these muscles, resulting in itchiness. A good chi flow will clear the “stale” energy, eliminating the tightness and rigidness as well as itchiness.

Such discomfort naturally makes it difficult for you to meditate. In fact if you stubbornly persist to meditate in such an adverse condition, it would bring your harmful effects instead of benefits. One should be healthy and fit physically, emotionally and mentally before attempting serious meditation.

Practising chi kung is an excellent way to overcome your health problems and enhance your meditation. Indeed, chi kung itself is meditation. When you practise chi kung, you work on both your energy and mind. Of course you have to practise real chi kung, and not some gentle physical exercise that claims to be chi kung.

Question 8

Are the lessons difficult to learn? I may have difficulties learning as I am slow to catch up, and I cannot concentrate well since I get distracted with my body discomfort.

Answer

The lessons are easy to learn — if you learn the exercises from a master who teach them as chi kung. In fact they are so simple that on-lookers may wonder whether they work.

On the other hand, many of my students have expressed amazement that these apparently simple chi kung exercises can produce such profound results. Students who had suffered from so-called incurable diseases recovered after a few months. Students who came with clutches walked away after the course without clutches. Students who had practised other forms of chi kung for years but had no experience of chi, found chi surging and flowing inside them in the very first lesson.

A big problem, which is not obvious to many people, is that because the exercises look simple, and are actually simple if learnt from a master, some people learn from books or videos, or from mediocre instructors. The exercises are still simple, but they have lost their essence and are performed not as chi kung but as physical exercises. The amazing results, of course, will then be missing.

The difficult part is not in the learning, but in your own practising. If you practise consistently what you have learnt in the course — 15 minutes a sessions, two sessions a day — you would overcome your health problems in a few months. If you practise off and on, or do not practise, you will still have your health problems even though you may have learnt well.

A basic tenet in Chinese medical philosophy is that all treatment starts from the heart, which means the mind in English. Chi kung masters have advised that to have good result you need to have three “hearts” — the heart of confidence, the heart of determination, and the heart of perseverance. You need to be confident of yourself, be determined that you will overcome your problems, and persevere in your effort. If, even before you start to acquire the techniques and skills that will help you to overcome your problems, you cast doubt on your ability, you only make things difficult for yourself.

Question 9

What happens if I still do not master the techniques taught at the end of the lessons?

Answer

A comforting point is that the chi kung you are going to learn in my intensive course is so powerful that even if you could perform a quarter as well as expected you would still overcome your health problems. This is no exaggeration. Shaolin Cosmos Chi Kung is meant for top level martial art and spiritual cultivation. Overcoming health problems is just a starting stage.

Do not ask rhetoric questions that deter you from your goal, just get on with the task that leads you to your goal of overcome your illness. First, find out what means are available to overcome your problems. Find out the credentials of the doctor, therapist or master who is going to help you, and more importantly find out the actual results he has produced. This gives you the “heart of confidence”.

If you have to learn a technique to overcome your problems, do not, — even before learning — question whether it is difficult to learn or you are too slow to learn. Whether it is difficult or you are slow, you still have to learn it if it is necessary. If it turns out that the technique is difficult and your are slow, then you will have to put more time and effort. You have no choice if you really want to get well. This is the “heart of determination”.

If it is required to undergo a particular treatment or practise a particular technique daily for six months to get well, then you have to take that treatment or practise that technique daily for six months. This is the “heart of perseverance”. You have no choice. If after three months you choose to stop the treatment or practise only when you like, you may not get well.