SELECTION OF QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS

DECEMBER 1999 PART 2

In traditional kungfu training, free sparring is used to confirm — rather than teach — combat efficiency. Hence, free sparring comes at the end, not the beginning, of combat training.

Numerous methods are used, and practising combat sequences is one main method. A primary function of practising pre-arranged combat sequences is to enable students to be so familiar with attack and defence movements so that when they are attacked, even not in any pre-determined manner, they can respond effectively and spontaneously.

Obviously anyone asking his students to put on boxing gloves to punch and kick one another freely has no idea of this important aspect of traditional kungfu training.

Question 1

I love martial arts, and in the past two years I have studied Bruce Lee's Jeet Koon Do, and Wing Chun.

— John, USA

Answer

Jeet Koon Do and Wing Chun are very effective martial arts. If your main purpose is combat efficiency, they are excellent choice.

But if you are looking for other dimensions like internal force training and spiritual cultivation, you may find arts like Shaolin and Taijiquan give you more room for expansion.

This, of course, is strictly my opinion. Many other experts, especially Jeet Koon Do and Wing Chun masters, will have different opinions, and you should also listen to their views.

Moreover, my opinion above is given relatively. If we compare a Wing Chun exponent who has trained “inch force” with a Shaolin or Taijiquan exponent who only performs external forms. the Wing Chun exponent has much more internal force.

Question 2

I would like to study more types of Chinese martial arts, because as someone who has spent a while reading and studying self-defense, the Chinese arts seem to be some of the best.

Answer

There are many good reasons to say Chinese martial arts are the best. First we list out the criteria for comparison, then we compare the various martial arts.

Different people, understandably, may hold different criteria, but it is reasonable to assume that most will agree the following criteria are significant: combat efficiency, health and vitality, history and philosophy, spiritual cultivation.

Because there is a far greater range of techniques and force training in the Chinese martial arts than in any other martial arts, it is logical to conclude that the Chinese martial arts have the greatest range for combat efficiency.

This is not to say that a Chinese martial artist is necessarily more combat efficient than a martial artist of other systems, because one who trains well in two or three techniques and force development methods can be better than another who trains badly in thirty or forty techniques and methods.

This actually is the de facto situation today. Generally a black-belt with three years' experience in any Japanese or Korean martial art is more combat efficient than a Chinese martial artist who only practises external forms for thirty years.

Chinese martial arts pay as much attention to health and vitality as to combat efficiency, whereas other martial systems neglect health for combat efficiency. The underlying principle in Chinese martial art philosophy is that if you want to be a good warrior, you must first of all have good health and vitality.

A person who has internal injury or is tensed and irritable, for example, cannot be a good fighter. In my opinion, the routine training itself of karate, taekwondo, kickboxing and Western Boxing, for example, brings about much internal injury and tends to make the practitioners tensed and irritable.

I recall a very meaningful comment my master, Sifu Ho Fatt Nam, once told me many years ago. “In Shaolin training even a weak, sickly person will eventually become strong and healthy; in the other foreign arts a practitioner hurts himself even before he starts to spar with his training partner.”

There are many ways the practitioner hurts himself in his solo training. Damaging his hands and legs in hard conditioning, tensing his muscles in form practice, and screaming and grimacing to look fearsome are some examples.

Chinese martial arts pay much attention to chi, whereas other martial systems do not. Although the Japanese and Korean arts also talk about ki (their word for chi), from the chi kung perspective their chi training is superficial.

A karate or taekwondo practitioner, for example, soon pants for breath after training for about 15 minutes, and pour in water to quench his thirst. A Chinese martial artist may train strenuously for an hour and yet needs not drink any water.

A karate or taekwondo practitioner is tired out after training, and is left with less energy than when he started his session. A Chinese martial artist is fresh and has more energy than before he started.

The management of chi, or energy, in the Chinese martial arts not only enables the practitioners to develop internal force, but also contribute significantly to their health and vitality.

Chinese martial arts not only have the longest history, they also have been developed by the biggest population of the world. This tremendous time and volume have enabled the Chinese martial arts to develop a richness of philosophy which no other philosophies of other martial systems can ever compare.

For example, while other martial artists are mainly concerned with their immediate attack and defence, Chinese martial artists employ tactics and strategies. In other words, a Chinese martial artist does not merely strike an opponent with a punch or defend against his kick, but he will manoeuvre his opponent in such ways that he can use his strong point against his opponent's weakness.

Besides attaining combat efficiency, health and vitality, Chinese martial artists also cultivate spiritually. Some other martial arts like aikido and judo, and even karate and taekwondo, also mention spiritual cultivation, but there is a qualitative as well as quantitative difference between them and the greatest of the Chinese martial arts like Shaolin Kungfu and Taijiquan.

Indeed Shaolin Kungfu and Taijiquan were initially developed for spiritual cultivation; combat efficiency, health and vitality were later bonuses! Shaolin Kungfu and Taijiquan do not just talk about spirituality; their practice itself is a programme of spiritual cultivation. Hence, in Shaolin Kungfu and Taijiquan, as well as many other Chinese martial arts, meditation which is the training of mind or spirit, forms an integral part of the arts.

When you consider these criteria, you will find it justifiable to regard Chinese martial arts as the best. But you must be careful that if you want these benefits as described above, you must practise a genuine Chinese martial art that gives these results.

To practise a genuine Chinese martial art was a very rare opportunity in the past. That was one main reason why Chinese martial art students had great reverence for their teachers.

Today it is still a very rare opportunity, but it is easy to practise diluted Chinese martial arts which provide only external demonstrative forms.

There is another important point to take note. There is a crucial difference between studying and practising martial arts.

With the availablity of information today, studying a martial art — i.e. reading about it to understand it better — is easy. Practising it, even if you have the rare opportunity to learn it from a real master, demands much time and effort which most people are not ready to give.

Question 3

My interest lies solely in learning efficient and practical means of self-defense, not in sports, or fancy-looking techniques.

Answer

My definition of a martial art, Chinese or otherwise, is that it must be capable of self-defence. If some Shaolin or Taiji forms are meant for sports or as fancy-looking techniques to please spectators, they should be called Shaolin and Taiji sports or dance.

“Should” suggest an idealistic condition — they should but they are not. In everyday reality most Shaolin and Taiji sports or dance are still called Shaolin Kungfu and Taijiquan, often with the sportsmen and dancers being unaware of the situation.

But remember that self-defence is only one of the many benefits of Chinese martial arts. It would be unwise if you choose to ignore or neglect the other benefits.

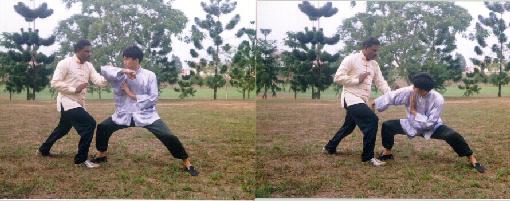

In the combat sequence shown in this webpage (please also see the photos above as well as below) Tai attacks Mogan with a thrust-punch. As soon as Mogan defends against the attack, Tai “leaks” his arm around Mogan's defending arm, and moves in shiftly to attack Mogan's solar plesus with an elbow strike.

Mogan pushes away the attacking elbow, but before Mogan counter-attacks, Tai "leaks" away from Mogan's hand and strikes Mogan's dan tian (abdominal energy field) with a reversed palm.

Question 4

I recently found a school teaching various Chinese martial arts. The instructor claims to teach Tai Chi, Xing Yi, Bagua, and Qigong. I am not familiar with any of these. I would greatly appreciate any advice you could give me.

Answer

Taijiquan, Xingyiquan and Baguazhang — or Tai Chi Chuan, Hsing Yi Kungfu and Pakua Kungfu — are three different forms of Chinese martial arts. They are generally regarded as internal styles because much attention is paid to energy and mind in their training. Qigong — or chi kung — is the art of energy management.

Qigong is extensively used in genuine Taijiquan, Xingyiquan and Baguazhang. Indeed, if these arts are practised without qigong, they would degrade into Taiji dance, Xingyi gymnastics and Bagua dance.

On the other hand, qigong is also used for non-martial purposes. There are countless different qigong exercises. Many people practise qigong for health and vitality, and some for better sexual performance, enhanced intellectual pursues, and spiritual development.

Taijiquan, Xingyiquan and Baguazhang are by themselves great, profound arts which need many years of dedicated training to master. If someone claims that he can teach all of them, I would suspect whether he has mastered any one of the arts.

My opinion is that probably he has superficially acquired some external forms of the three arts. Had he gone deep enough in any one of them, he would have derived so much benefit from it that he would consider it not cost-effective to attempt the other two.

But if you just want a taste of the three arts, especially only their external forms, it would be easier for you to learn all the three from one teacher.

Question 5

You said in your Nov-Dec 1997 question-answer series that “If you practise genuine Tai Chi Chuan, you should be able to take on a black-belt within one year.” I found this surprising, as I've also seen the importance you put in gradation for the learning of the art of Tai Chi, and the general complexity of it.

— Lee. Belgium

Answer

It is not only possible, but actually feasible, for a student trained in genuine Tai Chi Chuan to take on a black-belt within one year, and most likely the Tai Chi Chuan student will be the winner.

It is surprising to most people because they do not have any idea how effective and powerful genuine Tai Chi Chuan is. They imagine genuine Tai Chi Chuan to be just something better than the type of “Tai Chi Chuan” they normally see, which for convenience we shall refer to as Tai Chi dance.

This line of reasoning which presumes that genuine Tai Chi Chuan is perhaps a few times more effective for combat than Tai Chi dance, is not valid because the purpose and nature of training in genuine Tai Chi Chuan are totally different than those in Tai Chi dance.

In Tai Chi dance you learn to be graceful and elegant, and to relax and socialize. You may learn Tai Chi dance for 30 years or for your whole lifetime, yet you will be unable to take on a black-belt, simply because you have never learnt how to fight nor ever developed the force and skills for fighting.

In genuine Tai Chi Chuan you purposely learn to fight and develop the force and skills for fighting, besides attaining good health, vitality, mind expansion and spiritual joy.

The next question to consider is whether a year of daily genuine Tai Chi Chuan training is sufficient to attain a level of combat efficiency comparable, or superior, to one attained by a black-belt.

It takes about 3 years to attain a black-belt, but many black-belts do not train everyday, they normally train for 2 or 3 sessions a week. Assuming that a session consists of one hour, a black-belt would have trained for between 300 to 450 hours, whereas a genuine Tai Chi Chuan practitioner would have trained for 360 hours. In terms of hours, both would have trained for about the same time.

But in any art, the result obtained from an hour of training everyday for a total of 360 hours a year, is much better than training intermittingly (i.e. a day of training intercepted by two or three days of non-training) for a total of 360 hours or even 450 hours in three years.

But much more important than the actual time spent, is the nature of training. Moreover, we must also remember there are black-belts who train diligently everyday.

As you have observed correctly, the techniques and training methods in the black-belt arts are simplistic compared to those in Tai Chi Chuan. If you examine sparring sessions in karate and taekwondo, even amongst black-belts, their attacks consist mainly of straight-forward punches and kicks, and there is little or no attempt to defend, except some occasional jumping away.

In most cases the two combatants go in to punch and kick each other. In Tai Chi Chuan, we not only consider using the best techniques of the situation for attack and defence, we also go beyond techniques to consider tactics and strategies. Freely exchanging punches and kicks is unthinkable in Tai Chi Chuan combat, because a single strike may maim or kill.

If a black-belt wishes to increase his power, he normally strikes his hands or legs against a sandbag or a pole. If he wishes to increase his stamina, he skips or jogs. This is actually not increasing power or stamina; it is merely conditioning.

He conditions his hands and legs so that he will not feel pain when he strikes; he conditions his heart and lungs so that these organs can overwork when he stretches himself to his extreme.

Not only such methods are detrimental to health, he soon comes to a limit on how much his hands and legs can stand pain, and how much his organs can overwork.

Increasing power and stamina in Tai Chi Chaun is totally different. Instead of toughening his hands and legs, a Tai Chi Chuan practitioner increases his internal force and enhances his mind so that when power is needed for attack and defence, or for his daily work and play, he channels the necessarily force to where it is needed. To improve stamina

- he first strengthens his heart, lungs and other organs with appropriate qigong exercises;

- improves his efficiency of exchanging toxic waste with cosmic energy:

- regulates his breathing so that irrespective of the speed of his actions his breathing remains deep and gentle;

- stores some energy at his abdominal dan tian (or energy field) so that at all time this surplus of energy will prevent him from panting.

This may sound like a fairy tale to those unfamiliar with internal arts, or those who perform Tai Chi dance, but it is true.

For the first few months, the Tai Chi Chuan practitioner cannot even take on a blue-belt, because this is a time when he builds his foundation, such as clearing his lungs of stale air that has been clogging his air sacs for years previously, and building his internal force at his abdominal dan tian so that he can use it later.

After about six months, when he has built some foundation and has learnt some useful combat techniques, he can practise sparring.

The attacks of a karate or taekwondo black-belt, while formidable to an untrained person, are actually quite straight-forward, consisting mainly of punches and kicks, with little or no tricky moves.

Fighting a judo black-belt is much easier. He has to hold you and try to off-balance you before he can execute a throw. A Tai Chi Chuan exponent is well balanced and has good stances; he will probably throw the judo exponent off ground instead. Fighting an aikido black-belt is also not difficult. An aikido exponent has to make a few preliminary movements before he can execute an effective throw or lock, and he usually waits for the opponent's attacking moves. A Tai Chi Chuan exponent can feign an attack, lets the aikido black-belt make his preliminary movements, then strikes him down before the preliminary movements are completed.

The most formidable black-belts for the Tai Chi Chuan practitioner with just one year's training, probably come from jujitsu. Unlike the other black-belts mentioned earlier, a jujitsu black-belt does not fight as in sports but as in real combat.

A judo black-belt does not normally kick you, a taekwondo black-belt does not throw you onto the ground, nor a karate black-belt holds you in a lock, because forbidden by their sport rules, they are not trained to do so. But a jujitsu black-belt is not restricted by safety rules; he may grip your groins or pierce at your eyes. Nevetheless, the Tai Chi Chuan exponent, trained for real life-death fighting, can still take on a jujitsu black-belt comfortably. There are numerous advantages for the Tai Chi Chuan exponent. He has better stances, is generally more balanced, does not go out of breath as easily, has internal force, and employs tactics and strategies besides techniques.

Yes, gradual progress is important in any martial art. This means one does not train internal force for one week, then expects to be forceful the next week.

It also means one does not learn Tai Chi Chuan forms at one stage, then immediately jumps into free sparring at the next stage. Internal force training has to be practised everyday for the whole year. After learning combative Tai Chi Chuan techniques, one has to go through a few other steps before free sparring can be attempted.

Practising daily for one year is sufficient to graduate from a beginner's level to a level where taking on a black-belt is not difficult. But don't be mistaken that this is a high level. Even in the Japanese and Korean martial arts, attaining a black-belt first dan signifies that the practitioner has completed his novice training in the coloured belts and is now at his first level for more serious training.

Question 6

I guess what you meant was a year of intensive practice, like 8 hours a day six days a week.

Answer

You have guessed wrongly. It is just an hour a day, but everyday of the year.

The mode of training is also quite different from what many people imagine a Tai Chi Chuan session to be. Typically it is as follows. 15 minutes of zhan zhuang to develop internal force. 5 minutes of going over some Tai Chi Chuan patterns. 20 minutes of practising over and over again selected combat sequences. 10 minutes of free sparring, if applicable. 5 minutes of free energy flow. 5 minutes of meditation.

In a year, the practitioner will have practised selected combat sequences and their variations thousands of time, as well as have developed some internal force. When a black-belt attacks him, the black-belt is most likely to use some of these sequences, and the Tai Chi Chuan practitioner will respond appropriately and spontaneously.

Question 7

I was so excited about Chi-Kung that I didn't know I could not practice on a ship in the middle of Alaska. I began having constipation problems and some fevers. I used to wake up and start to feel a lot of fear for nothing.

I started having breathing problems like asthma, weakness, sourness, dried mouth, gastric problems, pain near the right groin, etc. My heart starts to throb faster even if I do just one repetition.

I tried doing “Lifting the Sky” slowly and softly but it seems to be hard. I have been practising abdominal breathing on bed because it is pretty hard doing it while standing up, and doing like 12 minutes or more of the position called “three circles”.

Sifu I would love to go and see you but unfortunately I don't even have money for the airplane ticket. If you could give some advice and a program to follow I would be happy and grateful.

— Sinuhe, Mexico

Answer

You realize that learning chi kung incorrectly can bring serious harmful effects, which you yourself are suffering from, but you don't seem to learn from your experience.

I can e-mail you some correct chi kung techniques, but it is likely you will practise them wrongly again, just as you practised my chi kung exercises wrongly, presumably from my books.

The important thing is not whether you practise the correct exercises, but whether you practise the exercises correctly — on a ship or anywhere else.

“Lifting the Sky”, for example, is an excellent chi kung exercise to overcome your problems, but if you practise it incorrectly, it will make your problems worse. Abdominal Breathing and Three-Circle Stance are not suitable for you at present.

But don't worry, genuine chi kung will solve your health problems, but you have to learn it from a real master, and then practise it at least for some time under his supervision. This is a requirement you have to fulfill if you wish to get well through chi kung.

You are being naïve if you think that you can have the same result by learning from an e-mail — in the same way as you are being naive if you think you can cure yourself of a serious illness like a doctor does by your reading from a medical text.

Practising chi kung dance from bogus instructors may not make your problems worse, but it will also not help you to overcome your problems. If you cannot afford to learn from me, you can learn from any other masters. The training fee you pay, even if it is expensive, will still be cheaper than the price of your suffering and eventual medical treatment.

Mogan uses a “taming-hand” to intercept Tai's reversed palm strike. Following Mogan's momuntum, Tai “leaks” away from Mogan's taming-hand and strikes Mogan's right temple with a “hanging fist”.

This "leak" technique manifested in the three attacks by Tai (to Mogan's solar plexus, dan tian, and temple) is famous, though little understood, in Hoong Ka Kungfu. As soon as the opponent defends against an attack, the Hoong Ka exponent "leaks" or "flows" to another attack, using the defending momentum of the opponent. Those who (mistakenly) think that Hoong Ka Kungfu is only "hard" may be amazed at the effectiveness of this Hoong Ka "soft" approach.

Some people, especially those who rush into free sparring, may say that in a real fight an attacker does not attack you in a pre-arranged manner as in the combat sequence above. They fail to realize that practising combat sequence is not free sparring, but is one of many methods to help you to fight well when needed. This also leads to another important point, i.e. if you only perform combat sequence as a demonstrative form, you still cannot fight. You have to develop force and stamina, and combative skills like judgement, timing and spacing. These have to be learnt from a master, not from a webpage or a video.

Question 8

You said that you do not believe in the use of boxing gloves for sparring. How then do your students manage to spar without hurting each other.

— Jason, USA

Answer

It is illuminating to note that not a single kungfu master in the past used boxing gloves when sparring with other masters, sparring with his students, or when teaching his students sparring, and they did not hurt each other. Boxing gloves are meant for boxing or kickboxing, not for kungfu.

Karate, taekwondo, jujitsu, judo, aikido and hapkido do not use boxing gloves, and when their exponents spar, onlookers could tell their style from their sparring.

It is only in modernized, and often greatly modified, kungfu that boxing gloves are used, and when these kungfu exponents spar, they spar like boxers or kickboxers, or worse still like children.

My personal opinion is that, apart from special occasions, anyone — including a master — who uses boxing gloves in teaching sparring does not know how to use genuine kungfu techniques in combat, even though he may be a good fighter (using non-kungfu techniques).

Not only my students do not use boxing gloves for sparring, they do not have any special protection like knee-guards and groin-guards, and they spar on hard floors. Yet, serious injury resulting from sparring is nil. This is due to the following reasons.

-

They are fully aware that the purpose of sparring is to mutually help each other to improve combat skills, and not to out-do each other. Hence if one finds his partner too slow, he will purposely slow down his attack to accommodate his partner.

If he strikes his partner, this will end that part of their sparring practice, giving them no chance to proceed further. If he purposely slows down, he experiences one of those rare occasions when he can more perceptively observe how an opponent moves, thereby noticing weaknesses which he can exploit if he wants to.

- They have good control of their attack. They employ what is known in kungfu terminology as “dian dow wei zi” (or “tim tou wai tze” in Cantonese), which is “contact by merely touching gently”.

-

Their approach to sparring is systematic and methodical. They never jump into free sparring immediately. They go through numerous stages of pre-arranged sparring, then semi-free sparring so that by the time they practise free sparring they can effectively defend themselves.

Unlike in most other martial art schools where free sparring is the beginning and end of sparring, and where practitioners go in freely to punch and kick each other, in traditional Shaolin training, free sparring is the cummulation of a long series of various sparring practices, where practitioners test out and confirm — rather than practise — their combat efficiency.

In other words, in traditional Shaolin training, students (and masters too) do not use free sparring to practise combat; rather, they use free sparring to confirm that they are combat efficient.

But injuries sometimes occur, even in pre-arranged sparring, but they are usually not serious. They can be overcome in literally five minutes by performing appropriate chi kung exercises, especially “Lifting the Sky”. This solves about 80% of the injuries.

In the other 20%, I open the relevant energy points of an injured student, transmit some chi into him and ask him to perform a spontaneous chi flow exercise. In about 15 minutes his injury would be overcome.

On very rare occasions, I have to prescribe some kungfu medicine for an injured student to apply externally and take in orally. He would recover in one to three weeks.

In my kungfu training days I was once injured seriously. I was free sparring with my siheng, or senior classmate, who was even smaller-sized than I was. He gave me a double-punch; I gripped his two wrists with double tiger-claws, immobolizing his attack.

In my inexperience I thought that was the completion of a practice sequence. But he meant his attack to be a trap. He released my grips with a twist of his wrists and struck my solar plexus with a cup-fist at close quarters. Seeing that I could not defend the unexpected attack, he pulled back immediately, merely touching my chest with the fist.

Even for just a tap, he was sincerely sorry. I still remember that he said he thought I knew how to counter the attack because it was found in our Shaolin Pakua Set. I told him I had learnt the set but had not learnt that particular application. We thought nothing about the gentle tap; there was not even any mark on my skin, nor any pain.

But a few days later my eyes turned yellowish, and I could hardly speak. I knew immediately that I had sustained internal injury from my siheng's tap. I told my sifu, and he confirmed the injury. My siheng's internal force was so powerful that it distorted the energy field in my chest and caused some serious energy blockage.

My sifu applied some external medicine on my chest, and prescribed some internal medicine for me to drink. After a few days, my chest turned purplish black, as a result of the medication drawing out “dead blood” from my internal injury.

It took me many months of medication and remedial chi kung exercise to recover. Should anyone think that internal force is a myth, I can vouch from my personal, direct experience that it is true. Understandably many people will find it outlandish; I myself might not believe it if not for my own experience.

My siheng did not even strike me; he actually pulled back his punch. I reckon that if my siheng struck an opponent's solar plexis, especially with a phoenix-eye fist instead of a cup-fist, that person would die — not immediately, but after a few months, and he might not even know why.

This experience was an invaluable lesson to me — learnt first hand. Subsequently in my numerous sparrings and occasional fights, I made doubly sure I was safe before I released my guard.

Gradually I became so intuitively perceptive that later, on many occasions when I paused to explain finer points to my students during sparring but they unintentionally continued to strike me, I could still ward off their attacks.

Question 9

The sparring we do is not sparring in the true sense of the word. We are attacked once with any type of attack and we are expected to use the techniques we have learnt to defend ourselves.

Answer

This is one-step sparring, and is usually used at the beginning of learning to spar. But your approach is haphazard. In this case the defender will often be uncertain and hesitant.

A better approach is as follows. Decide on only one type of attack, and the defender knows what technique to use to defend against this pre-chosen attack. Practise this one-step pre-chosen attack and defence at least ten times before changing to another type of attack and defence.

The onus of this training is not learning to use which technique to defend against an attack, but to develop the necessary skills like judgement, spacing and timing in using a pre-chosen defence appropriate for that particular type of attack.

Anyone with some experience of fighting will know that skills are much more important than techniques. This is probably the most important factor why kungfu practitioners today are generally no match against karate or taekwondo exponents. They know, in theory, hundreds of techniques but they have no skills to use even the simplest of techniques effectively.

Question 10

Currently I am practicing about 3-4 times a week, I want to get more serious about my practice. What is the maximum amount of time one should spend per week to get optimal results?

Answer

Maximum time and optimal results are philosophical concepts. In practice, they vary greatly from individuals to individuals and from situations to situations. Variables like knowledge and exposure, needs and abilities, resources and instructions are influential.

The maximum time and optimal results of someone who uses boxing gloves and hopes to match up to a karate black-belt are very different from those of another who emulates the classical kungfu masters.

If you use boxing gloves and training methods generally employed by most kungfu schools today, and if you train for two hours per session about 3-4 times a week, you can fight in six months, and can take on a black-belt in three years.

But if you continue training for 30 years you will not be much better in fighting; you may even be worse due to your advancing age.

If you follow traditional kungfu methods which are rare nowadays and which do not use boxing gloves, and if you train for two hours per session about 3-4 times a week, you cannot fight in six months, but you can handle a black-belt comfortably in three years.

If you continue training for 30 years you can handle a black-belt like a child, and you will have better health and vitality than when you began training 33 years ago.

As most people today are so used to kungfu that has been much modernized and modified that it serves the purpose of gymnastics and dance more than a combat art, they will find it hard to believe how a traditional kungfu master can handle a black-belt like a child.

Indeed the opposite situation is more common. Many "masters" teaching modernized kungfu, such as wushu and tai chi where sparring is never a part of their training, may be quite helpless when attacked by black-belts.

But you may have a good idea if you look at it this way. After 30 years of training where internal force and sparring are crucial components, the traditional kungfu master will have become extremely powerful and have gone through millions of times combative movements black-belts typically use.

The attacks of a black-belt, while damaging to the uninitiated, are actually quite straight-forward. Hence when a black-belt attacks him, the traditional kungfu master merely handles the attacks as if they are part of his daily training routine.