STICKING HANDS AND NO-SHADOW KICK

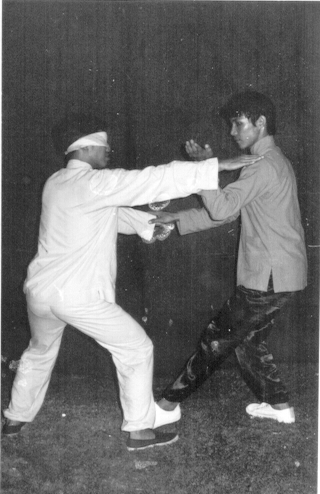

An old picture showing Grandmaster Wong practicing Sticking Hands while being blind-folded

Question 6

I was recently watching a Kungfu film that focused on Wing Choon, and one of the characters made an interesting comment regarding Sticky Hands practice. The teacher said to the student, "Do not follow your opponents movements. Follow his shadow." The teacher was telling the student to follow the opponent's intention, rather than his movements. Would you agree with this instruction for Sticky Hands? Or is this a fictional approach that was included in the movie?

I'm also curious to know if "shadow" is typically/traditionally used to mean intention, as in No Shadow Kick. Would this be a kick that is executed without any obvious intention to kick, or telegraphing the movement, thus making it difficult to block?

Sifu Matt Fenton

Answer

I would not agree with the instruction mentioned in the movie. There is some truth in the instruction at an advanced level but its meaning is not like what you mentioned.

The main aim of Sticking Hands is to train sensitivity of the arms so as to be able to deflect an opponent’s attack with the arms without having to look at the attack. The core of the training is with the attacker’s movements.

In kungfu context, “shadow” does not typically or traditionally mean intention. It means the withdrawing movement of an opponent, usually but not necessarily after an attack.

If an opponent attacks the practitioner’s head, regardless of whether the opponent’s intention is to attack the head and before he withdraws his attack, the practitioner must deflect the attack during Sticking Hands practice. He may dodge the attack instead of deflecting it, but still he covers the attack with his hand in case the opponent extends or changes his attack.

The attack may be a feint move. When the practitioner in his Sticking Hands training attempts to deflect the attack to his head, the opponent changes it to an attack to his body using a reverse ginger-fist, also called a leopard-fist (which is commonly used in Choe Family Wing Choon, but not in the popular Wing Choon styles practiced today). In his initial training the practitioner may be tricked. In this case, the opponent must not forget to guard his face with his other hand.

But eventually, as his deflecting hand is in contact with the opponent’s attack, the practitioner can sense the changing movement of the opponent and follows it, thus also deflecting the real attack after the feint one.

The arms of the two practitioners in Sticking Hands training are usually in contact. But there may be occasions when they are not. For example, an attacker may use the tactic of “one against two” to close the opponent’s two hands with his one hand, then execute a thrust kick. The responder may counter with a hand sweep.

Then, the attacker makes a feint move to attack the opponent’s head. The opponent raises his hand to deflect the attack. But before the arms come into contact, the attacker changes his momentum to attack the opponent’s body with a reversed ginger-fist. Initially, the opponent may be hit. But gradually, if the training is systematic, the opponent can respond spontaneously even when their arms are not in contact.

In our school, when we practice Sticking Hands we create a chi field that extends beyond our physical arms. Even when our arms are not in contact and we are blind-folded, we can pick up the movement, and later the intention, of an opponent in our chi field. This was the reason why some of our advanced students and instructors in the Special Wing Choon Course in Penang in 2010 reported to me that during free sparring when their eyes were open, they could respond more effectively by sensing than by seeing their opponent’s attack.

At this stage, the opponent’s movement and his intention are the same. He makes a feint move to attack your head, then changes it to an attack to your body because that is what he has intended to do. As our training is systematic and progressive, later you can also sense his emotions and other intentions. You may, for example, sense that he is nervous or confident. You may also sense that he is preparing to run away, or is about to press in with continuous attacks.

As the level of martial arts today is low, with many martial artists freely exchange blows with a shocking disregard to their own safety, many people may not believe in these higher aspects of kungfu. But some of our instructors and senior students told me that sometimes in free sparring they knew beforehand what attacks their opponents would make. They picked up their opponents’ intentions in their chi field or mind field.

George told me an interesting story some time ago. He was free sparring with Kai on an occasion not connected with Wing Choon Kungfu. They were in poise position. Suddenly George withdrew with his hand protecting his eyes. Kai then told George that he intended to execute “Poisonous Snake Shoots Venom”. Kai’s shen, which included his intention, was so strong, and George’s sensitivity so sharp that George could easily pick up Kai’s intention before Kai actually made the movement.

Had George practiced Wing Choon Kungfu, he would have the benefit of breadth and depth to exploit the situation. He would wait for Kai to make his move, then swiftly squatted down like a gorilla, as George is quite large in size, to pluck some peaches. Gorillas love peaches too. Kai, of course, could protect his peaches. He might, for example, lift up his leg to protect the peaches and then executed his world-famous kicks.

The above scenario shows the systematic progression of Sticking Hands training. If a teacher were to say, “Don’t follow the movement, follow the intention”, students would be confused. They may understand the meaning of the instruction but lack the skills to carry it out. Such an instruction is bad, but is better than an instruction commonly found in martial arts, “Put on your boxing gloves and fight”. The instructor submits his students, and the students submit themselves to being hit and punched when they are supposed to learn an art that prevents this happening!

Students practicing Sticking Hands while blind-folded during a Special Wing Choon Course in Penang in 2010

In kungfu context, “shadow” often refers to an opponent’s retreating movement. When an opponent attacks, you deflect his attack, with your hand still in contact with his arm. When he withdraws his arm, you follow the “shadow” to strike him. This is a manifestation of a saying commonly found in popular styles of Wing Choon, i.e. “loi lau huai soong, leik sau chiet choong”, which means, “When an opponent comes, retain him; when he retreats, send him away. If the arms lose contact, strike straight ahead.”

In Choe Family Wing Choon practiced in our school, this is only one of many combat principles. It is not the all-important principle that some practitioners of popular styles of Wing Choon think it is. Other important combat principles in Choe Family Wing Choon, which are also found in other kungfu styles, especially those from Shaolin, are “yow kiew kiew sheong ko, mo kiew shun shui lau”, which means “If there is a bridge, go along the bridge; if there is no bridge, follow the flow of water”, and “yow yein ta yein, mo yein choui ying”, which means “if there is form, strike the form; if there is no form, chase the shadow”.

When an opponent attacks, you counter-strike at the same time, with your attacking arm going over his attacking arm, thus deflecting his attack. This is going along the bridge. If he withdraws his arm, you still continue with your counter-attack. This is following the flow of water.

When an opponent attacks, you rotate your waist slightly to avoid his attack and simultaneously strike his attacking arm. This is striking the form when there is form. If he withdraws his arm, you immediately change from striking his arm to striking his body. This is chasing the shadow when there is no form.

In “no-shadow kick”, “shadow” does not refer to intention. Its meaning is literal. It means that the kick is so fast that it does not leave a shadow.

Actually, the effectiveness of the no-shadow kick depends more on tactic than on speed. I can speak with some authority because no-shadow kick is one of my specialties, the other being tiger-claw, both of which I learned from my Tiger-Crane Set. Those who will attend the Legacy of Wong Fei Hoong course at UK Summer Camp 2014 will have an introduction of both no-shadow kick and tiger-claw.

Although it is one of my specialties, as far as I can remember I used the no-shadow kick only once in my sparring and actual fighting in my younger days. Many years ago in Alor Star in Malaysia I used the no-shadow kick in the pattern, “Yellow Oriole Drinks Water”, on a master of Silambam, a classical Indian martial art. He was surprised by my dragon-hand form a few inches from his eyes. It was a few seconds later that he realized by no-shadow kick was just an inch from his groin.

In the Chinese language, “shadow” may sometimes mean “trace”. With a twist of semantics, though I don’t think this was its original meaning, “no-shadow kick” may refer to a skillful use of tactic that an opponent has no trace or awareness of the kick, even when it may not be executed fast.

I have demonstrated the no-shadow kick a few times in classes. There are quite a few no-shadow kicks hidden in our combat sequences. As they appear in the combat sequences, they are ordinary kicks. They become no-shadow kicks with the application of some appropriate tactics.

There is certainly a well-defined intention when executing a no-shadow kick, though the intention may not be obvious to an opponent. There is a signal when executing a kick, sometimes clearly shown. In fact there is a colloquial kungfu saying that “as soon as he moves his shoulder, I know a kick is coming”.

In a no-shadow kick the signal is minimized, or if it is obvious like in the case of a tiger-tail kick, the signal is made to be so misleading that an opponent does not suspect a kick is coming.

Talking about the tiger-tail kick, I now remember I used it as a no-shadow kick on another occasion on my sidai, or junior classmate, Ah Fatt, who was a master at the Chin Wah Hoong Ka Kungfu Gymnasium. During a free sparring session, I tempted him to attack me, then suddenly applied a tiger-tail kick that caught him in total surprise though he knew this technique very well. It was my skillful use of tactic. Both this event and the event with the Silambam master are recorded in my coming autobiography, The Way of the Master.

“Never block a kick” is good kungfu advice, as there are many disadvantages doing so. If he telegraphs his kick, like moving his shoulder, for example, let him kick and dodge it, simultaneously strike his kicking leg. He will find it difficult to defend against your counter.

No-shadow kick in Wing Choon Kungfu

The questions and answers are reproduced from the thread Wing Choon Kungfu -- 10 Questions to Grandmaster Wong in the Shaolin Wahnam Discussion Forum.

LINKS