WHAT IS YOUR DEAREST WISH?

"And may you be always guided by the Shaolin Laws."

Evening.

Evening on any countryside was almost always beautiful. The evening sun was just setting, creating a beautiful pattern of colours in the sky. Myriad birds were fluttering home to their nests, making a lot of chirpy-chirp-chirp noise.

Yang Shao Ming was thinking of home. He usually slept in comfortable beds in extravagant hotels, in pleasant rest houses, in friends' lavish guest rooms, sometimes on altars of deserted temples and benches of public pavilions or even at roadsides or on treetops when hot on the trails of wanted men. But none of these places he could call his home. He loved freedom, and he often associated freedom with birds flying in open skies. But now seeing birds returning to their nests made him think of home.

He had no home. He had no wife and no children. Only when you had a wife who cooked for you, who patiently waited for you to come home every evening, and children who made more noise than those returning birds, who tied you down to a family, only then could you say you had a home. Only then could you say you were blessed with the happiness of your home.

Home seemed so far away. Yes he once had a home, but it was so far, far back in time. He could almost not remember.

There were many children in a house so broken and shattered that it could no longer be called a house. There were eight of them; yes eight children, ranging in age from one to twelve, and they were often crying because they were always hungry, always insufficient to eat. The father wanted to give some of his children away; the mother refused, she preferred to starve together, to die together. She could not bear to see her own children, her own blood and flesh given away.

But the father had his say. The youngest four were given away to anyone who just wanted them, so that they would not starve. Poor though he was, the father did not sell any of them to rich landlords nor to brothels in town; he did not want his sons to grow up to become slaves for life, nor his daughters to become entertainment girls. That perhaps was the only virtue Yang Shao Ming could think his father had.

One day the father carried the fifth child on his back. The child had a high fever and was fading from consciousness to unconsciousness, and unconsciousness to consciousness. But he could dimly remember his mother's wailing. He could also remember his father carried him a long distance from home, and finally placed him at the doorstep of a small countryside temple. The father took out an old towel to wrap him. Then he hugged the child, and kissed him many times on his head and on his face. Then the father walked away, but he turned back a few times to look at the child. Finally the father turned and ran. The child was too weak to call after his father, too weak even to cry. The next moment he closed his eyes and slept.

He did not know how long he slept. When he opened his eyes, he saw a young monk applying a cool, comfortable piece of cloth on his forehead and face. Then a middle-aged monk sat on the edge of his bed and fed him gruel -- in fact, the monk did more, he fed him warmth and love.

"Sifu," the young monk said, "he's still very weak. Won't you stay for a few more days to nurse him?"

"I can't, Hung Yun. I have to leave early tomorrow morning. Poor boy, he is so weak and under-nourished. Since karma has brought us together, I'll carry him on my back, back to the monastery and teach him our Shaolin arts. Tonight I'll give him qi, so that he'll have enough energy to sustain the journey."

"May Buddha have mercy on him," Hung Yun prayed softly.

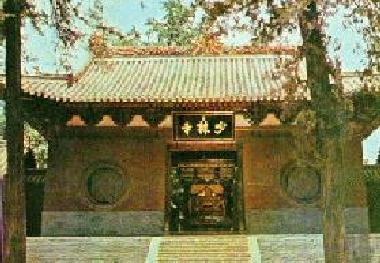

The boy stayed at Shaolin Monastery for eighteen years. He learned the Shaolin arts well and excelled in them. Most important of all, he learned to live meaningfully. He would be a monk, if not for an unfulfilled wish. When he first arrived at the monastery, the Venerable Ta Cher said he was too young to understand the meaning of becoming a monk.

"Let him grow up first, and only when he fully understands the purpose and obligations of monkhood, will he be offered the opportunity to choose to be ordained."

So the boy, like some other boys and young men in the monastery, remained as secular Shaolin disciples, and they were sparred some of the very strict regulations of monkhood.

When he was fifteen, after he had stayed in the monastery for ten years and observed at first hand the lives of the Shaolin monks, the master called the boy to his chamber one morning.

"Shao Ming," the master said kindly and earnestly, "you've been here for ten years. Are you happy with the kind of life here?"

"Yes, Sifu, and I'm very grateful to you. I'd like very much to be a monk."

The master, who was already sitting in the lotus position, closed his eyes for a few seconds to meditate. When he reopened his eyes, he asked, in a serious but gentle manner.

"Tell me, Shao Ming. What is your dearest wish?"

Without any hesitation, the boy said, "I wish to meet my father and mother, and my brothers and sisters again. I wish they are still alive and well."

The master closed his eyes again in meditation. Then he said, "You will meet them. But now is not the time. When you are ready, I'll send you out to search for them."

Eight years later the master called Yang Shao Ming into his chamber again, and said to him, "You are now ready to go into society."

"I'd like to remain here to follow Buddha's way."

"You're not yet ready to follow the blissful way of the Buddha. You still have your karma to complete. But the time has come for you to learn and practice the spirit of the Bodhisattva."

"How do I learn and practice the spirit of the Bodhisattva, Sifu?"

"Go into the lay world and spread compassion. And if you search hard enough, you may find your parents, and brothers and sisters. Only when your desires are spent, when you have paid all your karmic debts, you will be ready for the path of ultimate Enlightenment."

"I'll do as you command, Sifu."

"May blessings be with you. And may you be always guided by the Shaolin Laws."

LINKS