May 2007 (Part 2)

SELECTION OF QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS

Grandmaster Wong demonstrates the “press bridge” in the Iron Wire Set. A section of this set performed by Grandmaster Wong can be view here.

Question 1

I believe I heard somewhere that you prefer to have a structured, daily schedule. Can you please talk about the importance of having a daily schedule and any tips that may help us successfully implement and stick with our own (especially tips for handling disruptions such as travel or unexpectedly having to work late)?

— Chris, USA

Answer

Yes, having a structured daily schedule will help to save much time as well as to get maximum benefits from the practice, both in the practice session itself as well as the general programme of training.

Experience has shown that many students waste a lot of time thinking of what to practice next after they have completed one aspect of their training. Because they lack a clear cut schedule, they often practice haphazardly, spending too much time on what is relatively unimportant, neglecting crucial aspects as well as training redundantly.

For example, many students spend years on practicing kungfu sets, without developing force and practicing combat application, which are the two twin pillars of any kungfu training. Yet, after many years of practicing forms, their forms are not correct because they failed to master the basics like how to co-ordinate their body, feet and hands, and how to move with grace and balance.

Having a structured schedule will overcome these setbacks. But before we attempt to work out our schedule, we must have a clear idea of what the art we are going to practice is, what our aims and objectives of practicing are, and what resources we have to work on. Without such preliminary understanding, many people end up with form demonstration or Kick-Boxing though they originally aimed to practice Shaolin Kungfu or Taijiquan. Some of them, including instructors, have invested so much time and effort in their deviated practice that they even think or argue that form demonstration or Kick-Boxing is Shaolin Kungfu or Taijiquan!

Setting aims and objectives are important when constructing a daily practice schedule. It helps to make your practice very cost-effective. To set aims and objectives wisely, you need to be clear of not just what you wish to achieve but also what the art has to offer. Then you select from within the art the relevant resources for practice that best help you to accomplish your aims and objectives. Arranging this material into some systematic ways for practice makes up your daily practice schedule.

Allot time, say half an hour or an hour, for each training session, and give yourself, say, six months as a package to achieve your objectives. Your daily practice schedule may be the same every day if you have sufficient time in the session to complete the chosen material, or you may vary your daily schedule if you have a lot of material to cover.

Naturally, because of different needs and aspiration as well as developmental stage, different practitioners will have different schedules. Let us take an example of a student who attends regular classes from a Shaolin Wahnam instructor. He aims to have good health and vitality as well as combat efficiency. A good daily schedule is as follows.

Start with about 5 minutes of “Lifting the Sky”. Then spend about 10 minutes on stance training, followed by about 5 to 10 minutes of gentle chi flow. Next, spend about 10 minutes on the Art of Flexibility, alternating with the Art of 100 Kicks on different days, followed by about 5 minutes of chi flow.

Then practice a kungfu set. If he has learnt many sets, he may vary the set on different days. Depending on his needs, aspirations and developmental stage, in his set practice he may focus on correctness of form, fluidity of movements, breath control or explosion of force. This will take about 10 to 15 minutes.

For the next 10 or 15 minutes, he should practice his combat sequences. He may go over all the sequences he has learnt or select those he wishes to consolidate. He will practice them at the level he is at, such as merely going over the routine so that he will be very familiar with them, using steps like continuation and internal changes, or varying them in sparring with an imaginary opponent. He will conclude his training session with 5 or 10 minutes of Standing Meditation where he enjoys inner peace or expands into the Cosmos.

Another student who does not have the advantage of learning from a regional Shaolin Wahnam instructor, may have a very different daily schedule. Suppose he wants to attend my Intensive Shaolin Kungfu Course, but could not learn kungfu, even only outward forms, from a local teacher. So he has to learn the forms from my books, and familiarize himself with the combat sequences from my webpages.

His main aim is to prepare himself so that he can qualify to attend the Intensive Shaolin Kungfu Course. He has three main objectives — to be able to perform basic kungfu forms so that he can follow the course, to be familiar with the routine of the 16 combat sequences so that he can focus on developing combat skills instead of wasting time learning the sequence at the course, and to develop some internal force, especially at his arms, so that he can be fit for a lot of sparring. He allots half an hour a day for three months to achieve these objectives.

He should spend the first month focusing on the basics, i.e. the stances and footwork and basic patterns, and the other two months on familiarizing himself with the 16 combat sequences. Force training, including the Art of Flexibility, should be carried out throughout the three months.

He spends about 5 minutes on “Lifting the Sky” which he can learn from my books. He will probably not have any chi flow. For the first two weeks, he focuses only on the stances. He spends about 20 minutes learning how to perform the various stances correctly. At this stage, he needs not, and should not, remain at each stance for any length of time. In other words, this stage is not for zhan-zhuang, or remain at a stance for some time. His task is to be able to perform a stance, for a few seconds, correctly. Within two weeks he should be able to learn the correct positions of the stances quite well. For the remaining 5 minutes, he practices the Art of Flexibility.

For the next two weeks he focuses on moving in stances and performing basic patterns. By now he should be able to move into any stance correctly, though he may not be able to remain at the stance for long. He begins the session with about 5 minutes of “Lifting the Sky”. Then he spends another 5 minutes on performing all the stances correctly. The emphasis is on correct form, and not on remaining at the stance to develop force. Next, he spends about 15 minutes to learn how to move correctly in stances and to perform basic patterns. He should pay careful attention to waist rotation and body weight distribution so that he can move gracefully and without hurting his knees. He concludes the session with the Art of Flexibility. By the end of the month, he should be able to perform basic patterns in proper stances correctly.

For the next two weeks, he focuses on familiarizing himself with the 16 combat sequences as well as developing some internal force. He starts his session with stance training. Now, as the postures of his stances are correct, he focuses on remaining at a stance for as long as he comfortably can. This will take about 5 to 10 minutes. For the remaining 20 minutes, he practices the 16 combat sequences, starting with one and progress to all the others. He needs not worry about force and speed. His concern is to remember the routine of the sequences and perform the patterns correctly.

If he takes three days to learn and practice one combat sequence, he can complete the 16 sequences in 48 days, giving him a few days for general revision. He should learn and practice the sequences progressively, not individually. In other words, by the sixth day, he should be proficient in sequences 1 and 2, and by the ninth day be proficient in sequences 1, 2 and 3, etc.

Hence, if he follows these schedules for three months, he will be well prepared for the Intensive Shaolin Kungfu Course even though he might not have any kungfu experience before. On the other hand, someone who may have learnt kungfu for many years, where he only learns external kungfu forms, is ill prepared. This is a good example of cost-effectiveness. The smart student knows what he wants and plans his practice accordingly, whereas the mediocre student practices haphazardly without direction.

Question 2

Can you please explain the key differences between “long bridge, wide stance” (cheung kiu daai ma) and “short bridge, narrow stance” (dyun kiu dyun ma) systems - principles, usage etc?

— Sifu Pavel, Czech Republic

Answer

In “long bridge, wide stance” an exponent uses a wide stance and extend his hands fully in combat, especially in attacks but also in defences. In “short bridge, narrow stance”, an exponent uses a narrow stance and his attacks and defences are short or medium range.

Suppose a Boxer throws you some fast jabs. As he moves in to attack, you retreat slightly into a wide sideway Bow-Arrow Stance and simultaneously swing an outstretch arm diagonally upward at his attacking arm at its elbow, dislocating it, using the pattern “Yiet Sing Pao Chuei” (“One Star Throwing-Fist”) found in your 108-pattern Tiger-Crane Set.

As he bounces away to avoid your counter-attack, you move in with a wide Bow-Arrow Stance and swing your other outstretched arm at his body or arms, using the pattern “Yi Sing Pao Chuei” (Second Star Throwing-Fist”). This is an example of “long bridge, wide stance”.

Alternatively, as he throws you a right jab, brush off his jab with your right bent arm and simultaneously strikes his throat with your left phoenix-eye fist, using the pattern “Chor Hok Theng Fatt” (Left Crane-Thrust Technique) found in your Tiger-Crane Set. Please note that a skillful application of “waist-bridges-stances" is necessary as you brush off his fast jab while counter-attacking.

As he bounces away to avoid your Crane-Thrust or tries to protect himself by holding his hands in front, you can move in and brush away his hands with your left bent arm and simultaneously strike him with your right phoenix-eye fist, employing the pattern “You Hok Theng Fatt” (“Right Crane-Thrust Technique”). This is an example of “short bridge, narrow stance”.

Amongst Southern styles, Choy-Li-Fatt is well known for “long bridge wide stance”, whereas Wing Choon Kungfu for “short bridge, narrow stance”. Hoong Ka Kungfu uses both, but with a slight preference on “long bridge, wide stance”. But if we compare Southern styles with Northern styles, relatively the former uses more of “short bridge, narrow stance”, whereas the latter uses more of “long bridge, wide stance”.

Sifu Jamie Robson's response to Grandmaster Wong's attack shown above is an application of the skill of “Men Kiew” or “Asing Bridge” in Shaolin Kungfu

Question 3

What is the difference between Hung Ga “bridge hands”, Wing Cheun “sticking hands”, Taijiquan “pushing hands” and the hand techniques of long range systems like Hap Ga, White Crane, Choi Lei Fat?

Answer

“Asking Bridge” (“Men Kiu”), “Sticking Hands” (“Chi Sau”) and “Pushing Hands” (“Tui Shou”) are some of the ingenious ways in Hoong Ka, Wing Choon and Taijiquan respectively to train combat skills. In these methods, two practitioners keep their forearms in contact, and engage in attacking and defending moves.

The techniques and tactics they use are quite different. Hoong Ka “Asking Bridge” is relatively hard, and focuses on sinking an opponent's bridges. The two practitioners move above in various stances.

Wing Choon “Sticking Hands” are relatively stationary, with both practitioners at the Goat Stance. Their hand movements are fluid and in circles, though attacks usually come in straight lines.

Taijiquan “Pushing Hands” is practiced mainly at the Bow-Arrow Stance. There are two modes, stationary which focuses on developing skills, and mobile which focuses on applying techniques.

Hap Ka, White Crane and Choy-Li-Fatt are famous for their arm techniques, as distinct from using fists, elbows, fingers or palms.

Hap Ka, which means “Knight-Family Kungfu”, is a combination of Lama Kungfu of Tibet and Southern Shaolin, with a predominance on Lama Kungfu. Lama Kungfu makes extensive use of the arms like the long limbs of apes and wide wings of cranes.

There are a few different styles of White Crane Kungfu. The two that use arm techniques widely are the White Crane Kungfu from Tibet, and the White Crane from the Wing Choon District of Fujian Province in South China. Tibetan White Crane is similar to Hap Ka Kungfu where their practitioners swing their powerful arms frequently. They belong to the “long bridge, wide stance” category. Fujian White Crane uses the palms rather than the arms, and is of the “short bridge, narrow stance” category.

While Choy-Li-Fatt practitioners use their arms frequently, they use their fists, tiger-claws and palms extensively too. Choy-Li-Fatt is probably the most “long bridge, wide stance” amongst the Southern styles.

Question 4

I am currently reading the foreword by Grandmaster Lam Sai Weng (Lin Shirong) in the books written by his students (the foreword was published both in “Taming of the Tiger in Gung Pattern” manual and “Tiger and Crane” manual). Can you briefly explain the most important points he mentions, like waang-jik, tan-tou, jeun-teui, cheut-yap, sei dou, ng mun, sang sei ji lou, etc?

Answer

The foreword contains the essence of Grandmaster Lam Sai Weng's teaching, not just on kungfu but on living life rewardingly. It also exhibits typical points found in great masters' writings. It is short, of only one and a quarter pages, and concise, where a single word may carry a lot of information.

It is also arcane, hiding secrets in the open. The uninitiated may not find much information in the foreword, but the initiated can get a rich source of wisdom. How much benefit one can derive from this short foreword often depends on the knowledge and experience of the reader himself. “Waang-jik, than-thou, jeun-theui, cheut-yap” literally means “horizontal-straight, swallow-shoot, forward-backward, out-in”. This does not make much sense to the uninitiated.

Just before this, the Grandmaster mentions that first of all one must understand the principles. Next, practice the standard procedure. Then with correct effort and energy practice what is explained here, i.e. the Tiger-Crane Set and its combat application. Only then his progress will be remarkable.

This is what you have done. This is also what we in Shaolin Wahnam do. Hence, readers who wonder at our rapid progress may get the answer form these few words of the Grandmaster!

Grandmaster Lam, like most other great masters in the past who recorded the essence of their teachings, did not explain what “the principles” were. Why didn't he? It was because this foreword was not meant to be a self-taught manual for beginners. It was meant for his own students who had followed his teaching, theoretical and practical. Hence, the intended readers already knew what these principles were. This is an important fact many modern readers do not realize. It also explains why one must learn personally from a competent teacher if he wishes to have great results.

These principles the grandmaster mentioned concerned basic training. Basic training did not refer to combat application. It did not even refer to performing the Tiger-Crane Set in solo. It referred to stance training, footwork, body movement, breath control, being relaxed, being focused, and exploding force.

The student should follow standard procedure in his basic training, which is another way of saying he should not attempt to be smarter than his teacher by introducing material his teacher did not teach him. Many modern students attempt to be smarter than their teacher, though they may not realize it. They bounce about like Boxers when their teacher teaches them to move in kungfu patterns; they lift weights when their teacher teaches them to develop force through stance training.

When a student has become proficient in his basics, he proceeds to practice the Tiger-Crane Set and its combat application with “right effort and energy”. If he practices irregularly, it is not the right effort. If he becomes tensed and aggressive in his practice, he is not using the right energy.

Only when he has become proficient in the Tiger-Crane Set and its combat application, which is explained in the text along with the patterns individually, though it is not shown in pictures, the student progresses to understand the various points you have mentioned.

Briefly, the explanations of the points are as follows.

“Waang” or “horizontal” refers to various ways of defence, like intercepting, leaning and sweeping. “Jik” or “straight” refers to various ways of attack, like a thrust punch, a snap kick and a tiger-claw grip. “Than” or “shallow” refers to sinking back using footwork, body movement, hand techniques or some or all of these, to avoid the full force of an opponent. “Thou” or “shoot” refers to moving forward swiftly in footwork, body movement, hand techniques, or some or all of these to attack an opponent. “Cheut” or “out” refers to outward movements of techniques, stances, breathing, intention and other factors. “Yap” or “in” refers to inward movements of these factors.

These points are not exclusive; they may overlap or coincide. For example, striking an opponent, which is “shoot”, is often accompanied with an explosive shout, which is “out”. These principles are meant to enhance our performance, not to restrict it. For example, when an opponent executes a snap kick at your groin, you can respond with “False Leg Hand Sweep”, which may be rightly referred to as “horizontal” or “straight” depending on whether you wish to emphasize its defensive or attacking function. Arguing that it should either be “horizontal” or “straight” and not both, or that it is neither “horizontal” nor “straight” because its movement is actually diagonal, is defeating the purpose of using these principles.

“Saei for” means “four aspects” and here as used by Grandmaster Lam, they refer to “heart”, “eyes”, “hands” and “feet”. “Heart” means that the intention is decisive, “eyes” means the vision is clear, “hands” means the attack and defence are fluid, and “feet” means the movements are fast and agile.

“Ng mun” means “five gates”, and refer to top, middle, bottom, left and right. The Grandmaster explained that on top there were seven openings, namely two eyes, two ears, two nostrils and one mouth. In the middle there was the organ heart, or the solar plexus. At the bottom there were yin and yang, which referred to the sex organs and the anus. Left referred to the left side of the exponent, and right referred to his right side. In combat, an exponent using “four aspects” might attack the “five gates” of his opponent.

“Sang sei ji lou” means “the way of life and death”. The Grandmaster explained that based on “pat mein”, or “eight faces”, which refer to the eight compass directions, a combatant should evaluate the strength and weakness of his opponent as well as himself. He should avoid his own weakness, which is avoiding “the way of death”, and focus on his strength, which is choosing “the way of life”.

While these points are helpful for combat efficiency, I would not regard them as the most important. Other more important points include what Grandmaster Lam mentioned at the start as well as the conclusion of this short piece of writing.

Right at the beginning, the Grandmaster said that “While there is cultural achievement, martial preparation must not be lacking, because martial preparedness gives cultural achievement its backing.” This statement may be interpreted in different ways.

One example in personal lives is that if you wish to be successful in your career, you must be prepared to work hard — and smart. Another example applicable to public affairs is that if we want peace, we are unlikely to achieve it through merely talking, we must be militarily strong to enforce it through war if necessary.

At the end, Grandmaster Lam said that kungfu is not just an art of combat, but also an art of good health. We not only train to be physically and spiritually strong, but also by nourishing our spirit, training our body and nurturing our energy, we have good health and longevity. By penning these words, the Grandmaster hoped this national treasure would be passed on to posterity.

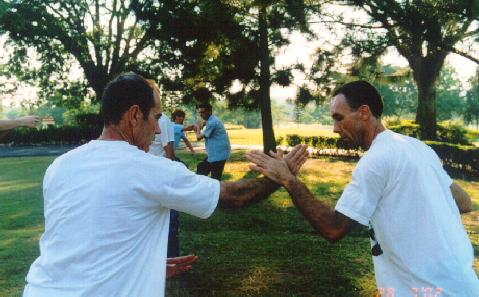

An old photograph more than 30 years ago showing Grandmaster Wong practicing Wing Choon “Chi Sau” or “Sticking Hands” with his classmate, Sifu Koay Hua Peng

Question 5

I would like to ask you again about the 12 bridges of Hung Ga system. Can you please give a brief description with practical examples from “Iron Thread Set” and usage?

Answer

Hoong Ka Kungfu is famous for its “bridges”, or powerful forearms. The master best known for his powerful bridges was Thit Kiew Sam. It was recorded that he could let six able-bodied adults hang on each arm, yet walked for over a hundred steps.

How did Thit Kiew Sam train to have such powerful arms? It was not through lifting weights and other mechanical means, but through practicing “Thit Seen Khuen”, or the “Iron Wire Set”. Thit Kiew Sam taught this set to Lam Fook Seng, who in turn taught it to Wong Fei Hoong, who then taught it to Lam Sai Weng, the patriarch of your lineage.

Through his generosity, Lam Sai Weng recorded this invaluable set for posterity in his classic, “Thit Seen Khuen” (“Iron Wire Set”), penned by his disciple Chu Yu Chai. As it was the custom amongst kungfu masters in the past, although a lot of information was recorded, this classic was concise, which means that only those with background knowledge could understand the information.

“Thit Seen Khuen” is an advanced kungfu set to train internal force, not just for combat efficiency but also for health, vitality and longevity. It also makes the body tough (but not massive or muscular), and the mind sharp and clear.

I practiced this set daily for some time in my young days, and can testify from my own experience that the internal force generated was tremendous. I would like to warn that it must be practiced correctly, preferably under the supervision of a master. Wrong practice can cause much harm, and it is easy to practice it wrongly.

One very common mistake is to practice “Thit Seen Khuen” as an isometric exercise instead of as chi kung or energy exercise. When one practices it as an isometric exercise, he tenses his muscles, whereas as chi kung, he is relaxed.

I was lucky because before “Thit Seen Khuen” I had practiced chi kung exercises like the Eighteen Lohan Hands, and therefore I knew exactly what practicing it as chi kung was like. Moreover, I had the great advantage of knowing Self-Manifested Chi Movement, which could clear away harmful side-effects even if I had practiced wrongly.

For those who may be interested, I have specailly prepared a short video clip showing how I perform a typical part of “Thit Seen Khuen”. The video clip can be accessed here. The way I perform it, however, is slightly different from that shown in Grandmaster Lam Sai Weng's book.

The internal force derived from “Thit Seen Khuen” may be classified into twelve types, known as “twelve bridges”. These twelve types of force are summed up in a poetic expression as follows:

- Kong yow pik cheit fun ting chuin

- Tai lau wan chai ding thien khuen

Word by word it may be translated as follows:

- Hard soft press straight separate stable inch

- Lift keep circulate control match the cosmos

To understand these “twelve bridges”, it is helpful to know two points. One, the difference is in their application, not in their nature. It is actually the same force, but used differently. Two, the classification into these “twelve bridges” is not exclusive or rigid. For example, if a particular pattern is used to train or apply hard force, it does not necessarily mean that the same pattern cannot be used to train or apply soft force. Or, if a force is hard, it does not mean that it cannot be soft too.

An analogy may make this clear. The electricity that we use in our house is the same electricity but it can be classified into different types according to its uses, like the electricity for lighting, for heating, for cooking, for powering our computers, etc. There are different ways to generate this electricity, like via coal, petrol, water or atom, just as there are different patterns to generate force in “Iron Wire Set”.

One particular way to generate electricity for lighting, for example, can also generate electricity for heating. It does not follow that if we use coal to generate electricity for lighting, we cannot use coal to generate electricity for heating. In the same way, if we use a particular pattern in the “Iron Wire Set” to generate “pressing” force, we can also use the same pattern to generate “straight” force.

Or, the electricity that we use to cook a meal, can also be channeled to work a computer. Similarly, the force that we use to execute a “fun bridge” or “separate bridge”, can also be channeled to execute a “ting bridge” or “stabilizing bridge”.

In the poetic expression above, “hard” and “soft” are two broad categories applicable to all the other types of force. In other words, the other types of force, like “press”, “straight”, “separate”, etc can be “hard” or “soft”. In the electricity analogy, all the various categories of electricity uses, like lighting, heating, cooking, etc, may operate as direct current or alternate current.

“Kong” or “hard” refers to hard force. But it is not mechanical or external. It is internal but relatively hard. Most of the force developed in “Tit Seen Khuen” as well in Hoong Ka Kungfu in general is hard. The pattern “Guarding the Dan Tian”, Pattern 10 in the set, generates hard force. Another example of hard force is “Control Bridges” in Pattern 19, where the hard force is used for controlling.

“You” or “soft” refers to soft force. One must remember that in kungfu, soft force can be very powerful. In fact, soft force is generally more advanced than hard force. Patterns like “Soft Bridge Inner Shoulders” (Pattern 26) and “Soft Bridge” (Pattern 29) are meant to develop soft force.

If you use your right hand to “retain” an opponent while you drive your left fist into his right temple, as in the pattern “Clamp Wooden Fist” (Pattern 47), you employ hard force in your attack. If you dodge your opponent attack and simultaneously thrust your finger thrust into his throat at close range, as in “Sideway Inch Bridge” (Pattern 33), you employ soft force.

One should note that it is not the forms of the patterns, but how the patterns are performed that determines whether soft force, hard force or any other types of force is generated. The same two forms, for example, may be used to generate hard force, in which case they would probably be called “Hard Bridge Inner Shoulders” and “Hard Bridge”.

“Pik” or “press” refers to pressing force. In the example given earlier where you “tame” your opponent's hands with a tiger-claw, and strike him with a thrust punch, you use pressing force in both your tiger-claw and your punch. And your pressing force in the tiger-claw and the punch can be both hard or both soft, or either one hard and the other soft.

Any pattern in the set can be used to generate pressing force, but the patterns “Guarding the Dan Tian” and “Lift Hands Protect Chest” (Patterns 10 and 11) are particularly useful. One may note that earlier I mentioned “Guarding Dan Tian” as an effective pattern for developing hard force, so he may wonder why now I mention it to be effective for developing pressing force. This is an example of dualistic or rigid thinking, mistakenly thinking that one particular pattern is used to develop only one particular force. Such rigid thinking seriously hinders an understanding of “Thit Seen Khuen”.

“Cheit” or “straight” refers to straight force, which is used in attack. The force shoots from you straight to your opponent. “Sideway Inch Bridge” (Pattern 33) is an effective pattern for training and applying straight force. “Black Tiger Steals Heart” is another example. Striking your opponent's temple, as in “Clamp Wooden Fist” above, is not using straight force, it is lifting force..

“Fun” or “separate” refers to separating force. An excellent pattern to develop separating force is “Separating Golden Fists” (Pattern 20). This force is very effective in releasing yourself from an opponent's grip. Suppose your opponent grips your right forearm as your executes a “Black Tiger Steals Heart”. You can release the grip with a small circular movement of your wrist using “fun” or separating force, then move in to strike his left temple with your right “horn-punch” using “tai” or lifting force, while you “tame” his hands with your left hand using “ting” or stabilizing force with the pattern “Clamp Wooden Fist”.

“Ting” or “stable” refers to stabilizing force. It is used to keep an opponent under control, like placing your hand over his arm to sense his movements and intentions. When an opponent strikes you, you lean your “Single Tiger” on his attacking arm with “ting” or stabilizing force. It can also be used to “tame” an opponent, like the example earlier where you strike an opponent's temple, The force is soft. A useful pattern to develop stabilizing force is “Stabilizing Golden Bridge” (Pattern 16).

“Chun” or “inch” refers to inch force, or force that can injure an opponent within a very short range. If, after stabilizing an opponent, he tries to move away, you may follow up with a strike within close range using inch force. “Double Inch Bridges” (Pattern 18) is a good example.

“Tai” or “lift” refers to lifting force. It is used when you raise your body or any part of it, like in releasing an opponent's grip. In an example where you lift your fist to strike an opponent's temple, you also employ “tai” or lifting force. “Sheltering Sky” (Pattern 60) is an effective pattern to train this force.

“Lau” or “keep” refers to retaining force. It is used to prevent an opponent from escaping or moving away, especially after he has moved in to attack. If you search the whole “Iron Wire Set” you may not find a single pattern that specially trains or uses this type of force. Yet, any one pattern in the set can train or use this force. Why is it so? It is because the force trained in the set is general, but can be used for any specific function, including retaining.

In the earlier example of “Clamp Wooden Fist” (Pattern 47), you employ “ting” or stabilizing force to “tame” or control your opponent so that he could not counter attack you. But if he tries to move away, you can still use the same pattern “Clamp Wooden Fist” and strike his temple with a “horn-punch” while locking both his arm with your bent arm using “lau” or retaining force.

“Wan” or “circulate” refers to circulating force, which of course is flowing. But it is not merely flowing, it connotes that the practitioner can direct this flowing force to wherever he wants. The pattern “Inner Shoulders Soft Force” (Patterns 51) trains this circulating force. But you will probably have a clear idea of circulating force from the patterns “One-Finger Stabilizes Middle Plain”, “Left Circulating of Soft Force” and “Right Circulating of Soft Force”(Patterns 7, 20 and 21) in the Tiger-Crane Set.

The usage of “wan” or circulating force is holistic. Unless you use muscular strength, any attack or defence you use involves circulating force — usually unconsciously when you have become proficient, but sometimes consciously. When you grip an opponent's vital points with a tiger-claw, for example, you direct your internal force using “wan” to grip him.

“Chai” or “control” refers to controlling force, which is used to control or subdue an opponent. It is similar, but not identical, to “ting” or stabilizing force. Controlling force is hard, whereas stabilizing force is soft. The pattern “Control Bridge” (Pattern 43) is meant to develop this controlling force. If your opponent uses his left hand to grip your right wrist, for example, you can reverse the situation with a small anti-clockwise circular movement of your right hand and grip him instead using “chai” or controlling force.

“Ding” or “match” refers to matching force. It is used to match or meet an opponent's force. In the set the pattern “Match Bridge” (Pattern 28) is meant to train this matching force. Matching force can be used in numerous ways. When your opponent strikes, you “lean” your tiger-claw against his attacking arm using matching force against his attack. Here you use minimal force to match his. Or you may use “Lift Pot to Offer Wine” (Pattern 48) to deflect his attack, then follow up with a strike to his face. Here you use more matching force to meet his attacking force.

The last two words in the poetic expression, “thien” and “khuen”, means the Cosmos. It is a poetic and symbolic way to conclude the poetic expression, suggesting that if you know and can skillfully apply the “twelve bridges” you can effectively handle any combat situations.

Question 6

Especially “lau” and “ding” are most discussed and misunderstood amongst Hung Ga practitioners. “Lau” (keep) is sometimes described as “flow” instead of “keep” in the old manuals. “Ding” is another mystery.

Answer

The “twelve bridges” of “Iron Wire Set” are often mentioned but little understood. A main cause for the misunderstanding or a lack of understanding is that many people view the concept from a dualistic or rigid perspective. One fallacy resulting from this misunderstanding is to mistakenly think that these “twelve bridges” or twelve types of force are exclusive, i.e. if one type of force is “lau”, for example, it cannot be “ding” or any other type of force. Another fallacy is to mistakenly think that a particular pattern develops a particular type of force.

There are patterns like “Ting Kiu” (Stabilize Bridge), “Chai Kiu” (Control Bridge) and “Chun Kiu” (Inch Bridge), which they reckon would be used to develop stabilizing force, controlling force and inch force respectively, though they may not know exactly how this can be accomplished. Then they are lost because there are no patterns named after many of the other types of force. There are, for example, no “Lau Kiu” and “Pik Kiu”.

But all these problems can be overcome once we have understood that unlike scientific terms which many Westerns are used to, kungfu terms are not definitive or rigid. (This will be an interesting topic for those in the habit of asking for scientific proofs for everything before they can believe it is valid.)

In science, for example, carbon dioxide is carbon dioxide, it cannot be something else. And a molecule of carbon dioxide is always made up of an atom of carbon and two atoms of oxygen. This scientific way of thinking may prompt some people to conclude that “lau” force must always be “lau” force, and cannot be something else. It also prompts them to think that a particular pattern that trains “lau” force would only train “lau” force and not any other types of force.

But in kungfu as well as in everyday life, this is not necessarily the case. For example, John is your friend, but he can also be a boss to another person. He becomes your friend because you met him at a party, but not everyone you met at the same party became your friend. On the other hand you can also make other friends in different situations.

“Lau” in the “twelve bridges” mean “keep” and refer to keeping force. But another word meaning “flow” also has the same pronunciation of “lau”. Hence, some practitioners may erroneously think that “lau” means “flowing force”, especially that “flow” or “leak” is an important Hoong Ka tactic.

Flowing force is important in any chi kung exercise. In the “twelve bridges”, flowing force is manifested in “wan”, which means “circulate” and refers to “circulating force”. Circulating force here is not just flowing force, it is flowing force directed by mind to flow to where the practitioner wants it to be.

“Leak” is an important tactic used in Hoong Ka. It means “flow over” (and sometimes under). Suppose you execute a thrust punch and your opponent deflects it with a taming hand, i.e. he pushes your punch downward. Following his downward momentum, you swing your fist, pivoted at the elbow, at his face, while taking care to guard his taming hand. This is an application of the “leak” tactic.

But in the case of the “twelve bridges”, there should not be any confusion because Grandmaster Lam himself confirmed in writing that “lau” means “keep”.

“Ding” means “match” and refers to matching force in the “twelve bridges”. Another “bridge” or force which sounds very similar is “ting”, which means “stabilize”. Not only the sounds are similar, the meanings are also related, thus adding to the confusion and mystery many practitioners have.

“Ding” or matching force is used when you match or in contact with your opponent, like when you ward off his attack. The confusion is compounded because you can use different types of force to match your opponent's force. In other words, depending on your purpose and other factors, your matching force can be “hard”, “soft”, “pressing”, “straight”, etc.

There is a pattern in the set called “Match Bridge” (Pattern 28). As the name implies, it is meant to train matching force. Here a practitioner stands at the left Bow-Arrow Stance with his left bent arm holding a fist in front of his face, while his right arm is straight with a One-Finger Zen form near his right thigh. One may wonder how this pattern develops or applies matching force.

This is a good example to show that it is not the outward pattern or form that matters. It is how the pattern is performed that determines what type of force is trained or applied in combat. In other words, this same pattern may be used to train or apply other types of force, like controlling force, circulating force, etc. On the other hand, any other patterns may be used to train or apply matching force or any other types of force. Nevertheless, some patterns may train or apply certain types of force better than other patterns.

Some patterns are specially named to remind practitioners of the types of force named, like “Match Bridge”, “Control Bridge” and “Inch Bridge”, so that they would not miss or forget them. If you understand all this, you would have a key to a better and holistic understanding of the “twelve bridges” in the “Iron Wire Set”.

Many people are puzzled and confused because of dualistic or rigid thinking. They mistakenly think, for example, that a particular pattern must be used to develop a particular type of force, and that a particular type of force, like “ding” or “chai”, cannot be another type of force, like “wan” or “lau”.

As a rough analogy, many people mistakenly think that if a particular course trains a person to be a lawyer, he must be a lawyer. And a lawyer cannot be a businessman. In reality, some people who underwent a course of law become businessmen. And some lawyers can also be businessmen at the same time or at different times.

Sifu Inaki of Spain and Sifu Rama of Costa Rica using the skills derived from Taijiquan Pushing Hands in their sparring

Question 7

I took your regional course in New York last year. I practiced everyday and I felt pretty good. Chi was flowing and my heart was smiling.

But about a month later, my Shaolin Kung Fu Shifu died. Then a month after that my grandpa died. I was so sad in those months that I couldn't smile from the heart. I just couldn't do my chi kung. But lately I'm done grieving and I started to do chi kung again. But it didn't feel like it was used to but I understand that I need more practice. At the same time when I feel so sad for my Shifu and my grandpa, I feel like it was a waste not practice during those months. How could I practice chi kung at a time with such grief?

— Peter, USA

Answer

I am sorry to hear of the passing on of your shifu and your grandpa. With both of your dear ones leaving you within the space of a short time, it is understandable that you feel sad, and your sadness affects your practice.There is a right time for every occasion. Although smiling from your heart is wonderful, when your loved ones passed away it is not the right time to do so. But this does not mean you could not practice chi kung. In other words, it does not mean one could not practice chi kung without smiling from the heart. In fact, many people practice chi kung without smiling from the heart, yet they obtain good results, though their results would be much better had they smiled from the heart.

On the other hand, practicing chi kung can cleanse away your grief. And when your grief has been cleared, you can smile from the heart again.

So, irrespective of whether you could smile or not smile, just carry on your daily chi kung practice. Soon you will find your chi flowing, your heart smiling and you feeling good again.

Question 8

How can both the Shaolin Kungfu and Jeet Kune Do techniques make one closer to enlightenment and what methods would be needed to reach that point?

— Kwabena, USA

Answer

First of all we need to be clear what "Enlightenment" means.Spelt with a capital E, Enlightenment means merging into Cosmic Reality. The enlightened being is enlightened to the cosmic fact that there is no differenentiation between him (or her) and everthing else. In Western terms it is returning to God the Holy Spirit. There is nothing else, only One, or God, or the Great Void. It is the highest spiritual attainment any being can ever achieve.

This concept of Enlightenment is vastly different from the concept of enlightenment (with a small e) that many people in the West have, as in the age of enlightenment. In the latter, much narrower and mundane sense, enlightenment means understanding, especially with reasons. If you are enlightened on a certain kungfu technique, for example, it means you now understand how that technique is performed or used, whereas earlier you were ignorant.

Shaolin Kungfu not only makes a practitioner close to Enlightenment, but it can actually enable him (or her) to attain Enlightenment. This, in fact, was the original aim of the great Bodhidharma teaching the Eighteen Lohan Hands, which later evolved into Shaolin Kungfu.

Shaolin Kungfu can do so because it trains not just the physical body and energy, but also the mind or spirit. With the supreme training of Shaolin Kungfu, with the help of energy flow, the practitioner's mind is cleansed of all defilement that he (or she) realizes that his personal mind is actually the Universal Mind, thus attaining Enlightenment.

At a much, much lower level, Shaolin Kungfu also leads to enlightenment. Shaolin Kungfu training clears the mind of thoughts, thus improving the practitioner's mental clarity, with the result that he understands the reasons behind events and processes. In other words he becomes enlightened.

The methods needed, therefore, are those that train the mind. Methods that only train the body or even energy are inadequate.

What are crucial in the methods are the skills rather than the techniques. If you have the appropriate skills, almost any techniques can be used.

For example, you can train your mind by performing a kungfu set, practicing stance training or engaging in combat application, which are all different techniques. Irrespective of the techniques, the skills are to bring your mind to one point, then expand it to nothingness.

Of course, here we are talking about genuine, traditional Shaolin Kungfu. By merely practicing the external forms of Shaolin Kungfu, without energy and mind training, one cannot attainment Enlightenment or even enlightenment.

I am not trained in Jeet Kwon Do, so I am not qualified to say how it can or cannot lead to Enlightenment or enlightenment. You have to ask Jeet Kwon Do masters to give you a better answer.

But basing on the little I know, I believe Jeet Kwon Do cannot make a practitioner closer to Enlightenment or enlightenment. The basic reason is that, like external Shaolin Kungfu forms, Jeet Kwon Do only trains the physical body, but not energy or mind.

This does not mean that one does not benefit his energy or mind in Jeet Kwon Do training. This is an incidental bonus, but is very different from training energy and mind on purpose.

LINKS

Selected Reading

- Amazing Experiences of Internal Force

- From Combat Sequences to Free Sparring

- Grandmaster Ho's Secrets in Countering Muay Thai Fighters

- Effective Tactics and Techniques against Boxers